Post Saubhagya – Moving Beyond Connections to Quality of Supply

Vivek Sen and Saloni Sachdeva, March 12, 2019

Distribution, the crucial link between power generation plants and end users, presents a complex challenge that India’s power sector is meeting with only qualified success. Despite being one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, India’s per capita electricity consumption is only about a third of the global average. The rural segment of the population has been most affected by the lack of proper supply and issues with reliability. Despite several schemes targeting enhanced rural electrification since 2005, in October 2017, more than 25 million households lacked access to electricity1.

In 2017, the Government of India launched the ambitious Saubhagya scheme, which aimed at electrifying all excluded Indian households by March 2019. Subsequently, the “Power for All” scheme was launched, which envisioned interventions across the power sector value chain including generation, transmission, distribution, energy efficiency, and improving the financial health of distribution companies. A prerequisite to power for all is connecting all households to the grid. Together, both Saubhagya and ‘Power for All’ were launched as complementary initiatives to closes the access gap. Both schemes cover urban and rural households with the goal of providing 24X7 power.

The last few years have changed the energy access story

Both Saubhagya and ‘Power for All’ envisaged an electricity connection for each household by drawing a service cable from the nearest electricity pole to the home, installing an energy meter and required wiring.

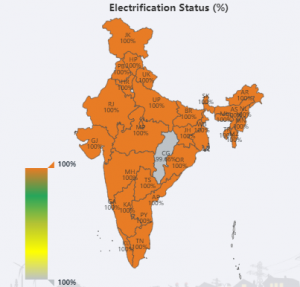

Saubhagya and ‘Power for All’ have seen tremendous success with household connections reaching 100% in all Indian states with the exception of Chhattisgarh where the current electrification rate is 99.65%. It is expected that Chhattisgarh will soon meet the target given the kind of impetus currently we are seeing.

According to a Financial Express report2, the pace of electrification was to be increased by 72% to meet the targets of 100% household electrification. The Saubhagya dashboard corroborates the tremendous pace of household electrification across the country.

The schemes helped provide each household physical connectivity with the grid, increasing the utilization of underutilized generation assets, thereby contributing to meeting the country’s climate change mitigation commitments. However more needs to be done.

Improving the access situation involves more than a physical connection to the grid. Quality of supply, particularly in terms of hours of supply, predictability of supply and steady voltage levels, must also be looked at. Post Saubhagya, with increased connections at the household level, there is still no guarantee that distribution companies will be able to supply power on demand. The financial position of distribution companies is already weak and with the sudden growth in demand because of an increased number of connections from low-paying consumer categories has resulted in additional financial stress on distribution companies. In addition to the mismatch between revenue and cost of electricity distributed, even the cost of providing a connection to each rural household has led to increasing the financial stress of the distribution companies. Further, the problem has been aggravated because of the lack of adequate and skilled manpower at the distribution company level to manage the increased burden of metering, billing, and collection and the increased O&M requirements.

Mini and micro grids contribute to increasing access to the underserved and unserved

Mini and micro grids have contributed greatly to improving the access situation even when the Saubhagya and ‘Power for All’ schemes were not launched. Small-scale localized power generation coupled with a distribution network can operate independently to provide a reliable supply of power with the additional benefit of reducing load on the conventional distribution network. Anchor load based models allowed productive activities and telecommunication to flourish even in the remotest of areas in the country.

However, with the Saubhagya and Power for All schemes in place, the narrative of mini and micro grids must evolve. The grid has reached to all parts of India, which will mean that the mini and microgrids will now have to act as a complementary solution to the grid supply.

It is a known fact that most of the private distribution companies in India are performing much better than publicly owned ones. The private sector has helped increase the efficiency of distribution operations of public distribution companies by handling responsibilities like metering, billing and collection functions.

In the same manner, a mini and micro grid operator, while being connected to the main grid, also assumes functions that can improve distribution operations in rural areas like metering, billing and collection and network management, apart from localised generation supporting the grid supply. This Mini-Generation and Distribution Model is now a viable option to further the energy access story.

A Public-Private Partnership construct will resolve operational and financial challenges

Capitalizing on private sector contribution (particularly from those well versed with the rural system like mini and micro grid operators) is a possible solution to overcome the grid’s commercial challenges. A public-private partnership (PPP) construct will be able to leverage the advantages of distribution franchisee models to reduce AT&C losses and improve customer service. In addition, it can help lead to broader outcomes such as efficient demand-side interventions for consumptive use, a strengthened focus on productive loads and increased efforts toward developing alternative tariff mechanisms including service-based charges and reliability charges.

This approach can help improve the operational and financial aspects of distribution companies while helping them meet their Universal Service Obligation (USO) of providing access and reliable power supply in rural areas. It can also contribute towards meeting the Government’s objectives and targets under the Saubhagya scheme, UDAY and Power for All programmes, by leveraging interventions therein.

From the consumer perspective, the assurance of reliable supply will unleash a positive cycle of increased demand and willingness to pay. This will enhance the viability of supply to rural consumers and the grid’s ability to invest in transmission lines and transformers. Greater and higher quality supply can motivate rural consumers to move from meeting just household energy needs to invest in productive loads to run commercial enterprises. This category of demand would have an even higher paying capacity.

Some of the very evident results that can be expected are:

- Reduced AT&C losses through improved metering, billing and collection, and improved customer experience.

- Increased reliability of supply, including attention to last mile O & M issues

- Strengthened focus on productive loads and efforts toward developing alternative tariff mechanisms including service-based charges and reliability charges.

- Meeting the Renewable Purchase Obligation (RPO) target.

- Mini and micro grid operators can have a reliable cash flow and increased customer base.

This tail-end DRE based PPP model can also help to meet the India’s targets for decentralized solar installations as well as its climate change mitigation goals.